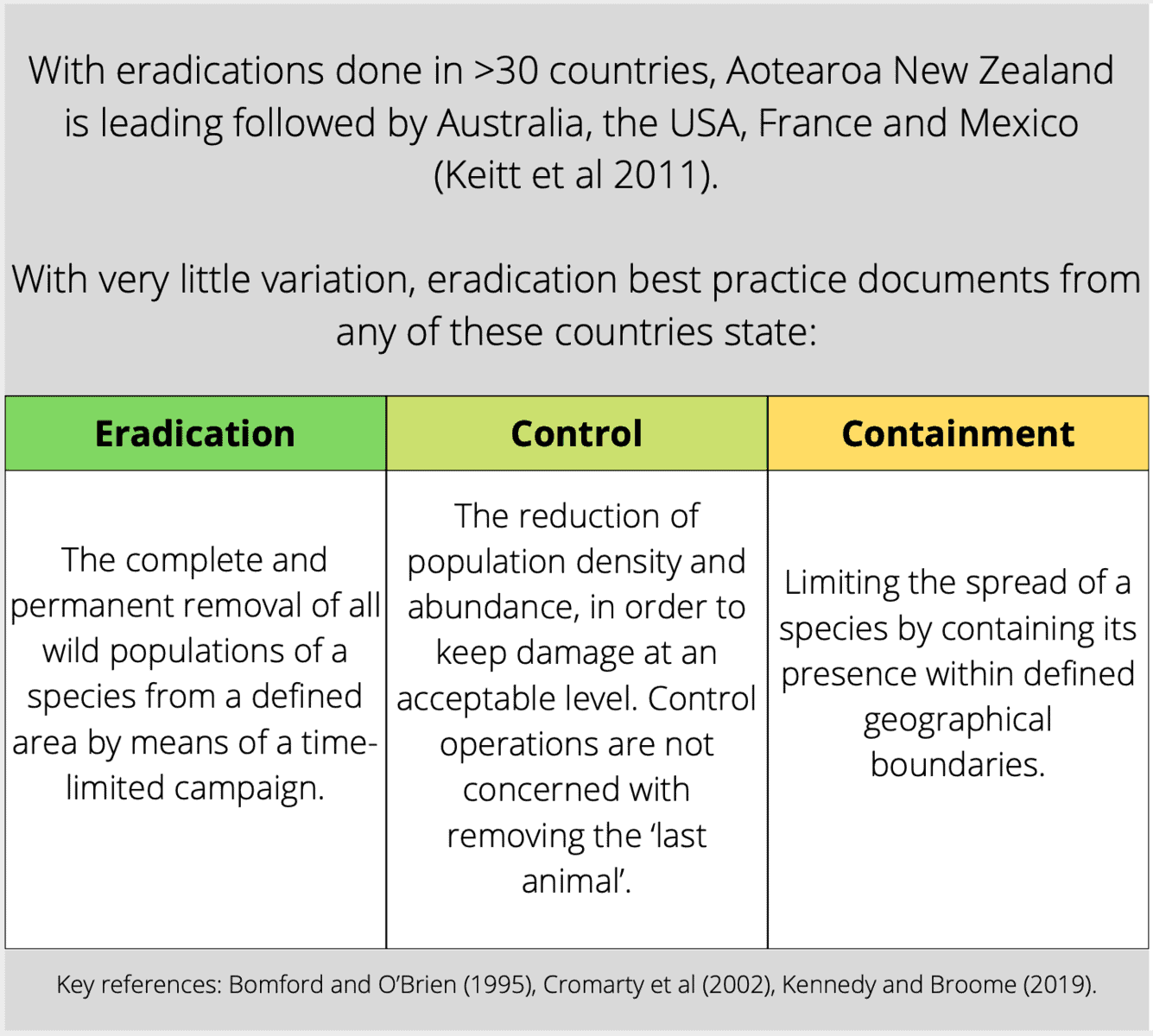

In the tradition of reo Pākehā, eradication is defined as the total removal of a thing, with an international consensus (from eight countries responsible for 80% of all pest eradications) of defining eradication as the “complete and permanent removal of all wild populations of a species from a defined area by means of a time-limited campaign.” When anything more than zero of that thing remains, is it still eradication, or is it something else?

“Some projects are not designed to achieve eradication, in which case the terms suppression or control are better descriptions,” says Natalie de Burgh, a biosecurity officer for Hawke’s Bay Regional Council. “This acknowledges that there will still be [some individual pest species] remaining in the landscape – although their detrimental effects will be significantly diminished.”

Unprotected by barriers (like bodies of water or inclusion fences) mainland projects can be especially tricky in this regard, with areas not achieving eradication, or only achieving it for certain periods before pest species re-infiltrate.

“There is currently a bit of a shift for mainland eradication projects to start using the term elimination rather than eradication to reflect this temporal instability,” says Natalie.

“It’s becoming more relevant to distinguish between projects with eradication as an objective and those with other more nuanced objectives. Both our original projects, Poutiri Ao ō Tāne and Cape to City are suppression focused projects – both of which are critical to ‘hold the line’ on biodiversity loss while we work on achieving eradication.”

Jo Ledington is Manager of Conservation and Restoration at Zealandia, Te Māra a Tāne. At the accoladed Pōneke (Wellington) sanctuary, mice have proven to be expert infiltrators, breaching the pest exclusion fence through their tenacity, and potentially via accidental catch-and-release by aerial predators (such as ruru). Because of this, Zealandia runs an annual programme to control these persistent rodents — which can imperil nestlings, mokomoko (reptiles) and aitanga-a-pēpeke (the world of invertebrates).

“We call it mouse control as we are aiming for suppression,” says Jo, of the yearly operation. “To me suppression denotes a repetitive process that reduces the numbers of individuals [of the target pest species]. Eradication is an action that removes all individuals permanently. After our annual mouse control, a suppressed population remains across the entire sanctuary, but in some smaller areas we do achieve zero mice for a short period of time. Over the year between control operations those areas are re-infiltrated.”

“I think we could be better at using the terms suppression and eradication more clearly so as not to undermine the success and purpose of either,” says Jo. “Each method has their own advantages. If we speak of a suppression project as eradication it appears to have failed, when in fact projects like DOC’s Tiakina Ngā Manu are integral for sustaining populations of threatened species in the wild while tools and techniques are being developed to achieve eradication. On the other side, eradication can seem incredibly expensive, but if it is well understood that this is a one-off large investment that can, for example, make a remote island predator free with no ongoing costs, the long-term cost is extremely small compared to suppression projects.”

“Suppression buys us time in that it reduces the loss of genetic diversity so the resultant populations will have a greater chance of survival long term and/or require less intensive management”

Jo Ledington

The Wellington region is starting to think about native species that aren’t regionally native,” says Jo, on the subject of the nuance needed as we develop new conservation perspectives and strategies. “We have a karaka (Corynocarpus laevigatus) wānanga coming up at Zealandia being led by mana whenua, Wellington City Council, and Zealandia to start this kōrero.”